Project Description

NEWFOUNDLAND

St. Mary’s Peninsula (part of Avalon Peninsula)

Tectonic Assembly of Newfoundland

fieldwork by James Howley

THE SCIENCE

Methodology in Howley’s Time

In the period from 1870 to the turn of the century, the geological sciences slowly grew. Although the interpretive aspects of the science were progressing, the fundamentals of field mapping in Canada remained essentially unchanged from the mid 1800’s.

Transportation away from the cities may have been by horse and wagon, but in the wilderness supplies were packed in by canoe and by foot.

In the Newfoundland interior, the MicMac First Nations were critical in enabling the mapping. They served as guides, canoemen, sherpas, chainmen, outfitters, and companions. Howley most certainly was indebted to them, but he also profoundly admired the MicMac, and it is said he become quite proficient in their language.

His sincere respect for the indigenous peoples led to a thorough study of the exterminated Beothuk nation, work that, somewhat ironically, he is best known for.

In the absence of adequate maps, it was necessary to deal with topography in advance of geology, and under Murray’s tutelage, Howley soon became a master of the prismatic compass (for bearings) , Rochon’s micrometer telescope (for distances), theodolite (for vertical and horizontal angles), sextant (astronomical observations), and pocket aneroid barometers (to determine elevations).

He also carried in the field with him a clinometer (a calibrated half disk with a plumb bob) for measuring the dip of beds, binoculars, an artificial horizon (a type of level), surveying chain, poles and hammers.

Interpretation by Howley

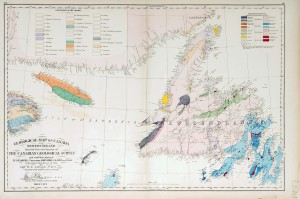

Howley was not the first geologist to inspect the rocks exposed along the coastline of the Avalon Peninsula. That honour goes to J.B. Jukes, a British geologist who in period 1837-39 examined some of the coastal exposures. His report and map were published in 1843, and later incorporated by Logan into his map of 1866 (Map 2). In the vicinity of Point Lance Jukes recognized rocks of Primoridal Silurian and Huronian age.

Howley investigated these same rocks in early June of 1870, and in his unpublished reminiscences recalled that “…In the evening a light breeze came up from the N.W. which carried us to Cape St. Mary’s but again died away and left us drifting about the Cape with the tide. There were a number of fishing boats on the ground about here and they greeted us with blowing of conchs, yelling and shouting etc.

All knew our skipper, Ambrose Walsh, and his boat. We were so close inshore that I could easily observe the rock structure especially by the aid of my binocular. We passed close to the Bull, Cow and Calf, and Point Lance, which appeared to be composed of trap rocks.”

The resistant igneous rocks that form the core of both Point Lance and adjacent Bull Island Point, and indeed are the reason that these headlands exist, were referred to as trap rocks by Howley.

The term is now obsolete but referred to dark, fine-grained igneous rocks, usually volcanic or shallow-seated intrusive dykes or sills. In basaltic lavas, the flow terminations are commonly abrupt and can be step-like. Trap is the Dutch word for stairs or steps.

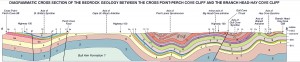

Recently published detailed mapping of Cape St Mary’s Peninsula, including Point Lance, by Fletcher (Map 4) confirms Howley’s initial observation; the headlands are composed of resistant, diorite to diabase-gabbro sills that have intruded Late Cambrian sediments, and have been folded by Siluro-Devonian deformation.

Current Interpretation and the Assembly of Newfoundland

James Howley would be quite amazed at how the geology of Newfoundland is presently interpreted! In his day he was of course aware of the diverse geology that makes up the island (from 1876 onwards he had mapped most of it himself!).

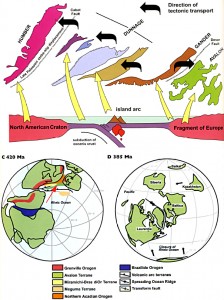

He would also have been very aware that the Cambrian and Ordovician strata exposed on the Avalon Peninsula, contained fossils very unlike those from similar age beds in neighbouring Quebec. With the maturation of ideas about plate tectonics in the 1970’s, the answer to this and many other geological riddles, soon became apparent.

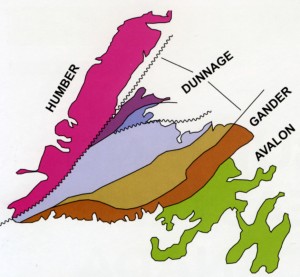

Newfoundland had been assembled over many millions years through the gradual docking or accreting of small plates or plate fragments (microplates) that had rifted, then drifted away, from larger continental masses, to the North American craton.

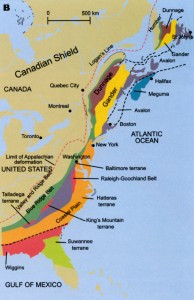

Geologists recognize four main accreted terranes in Newfoundland (Map 3), but the process was going on along the entire eastern margin of the continent, and is responsible for the Appalachian chain of mountains (Map 4).

The Avalon terrane joined rather late in the game (around 420 million years ago), as it rode the crustal conveyor belt associated with an old (pre-Atlantic) ocean basin called Iapetus.

James Patrick Howley

James Patrick Howley